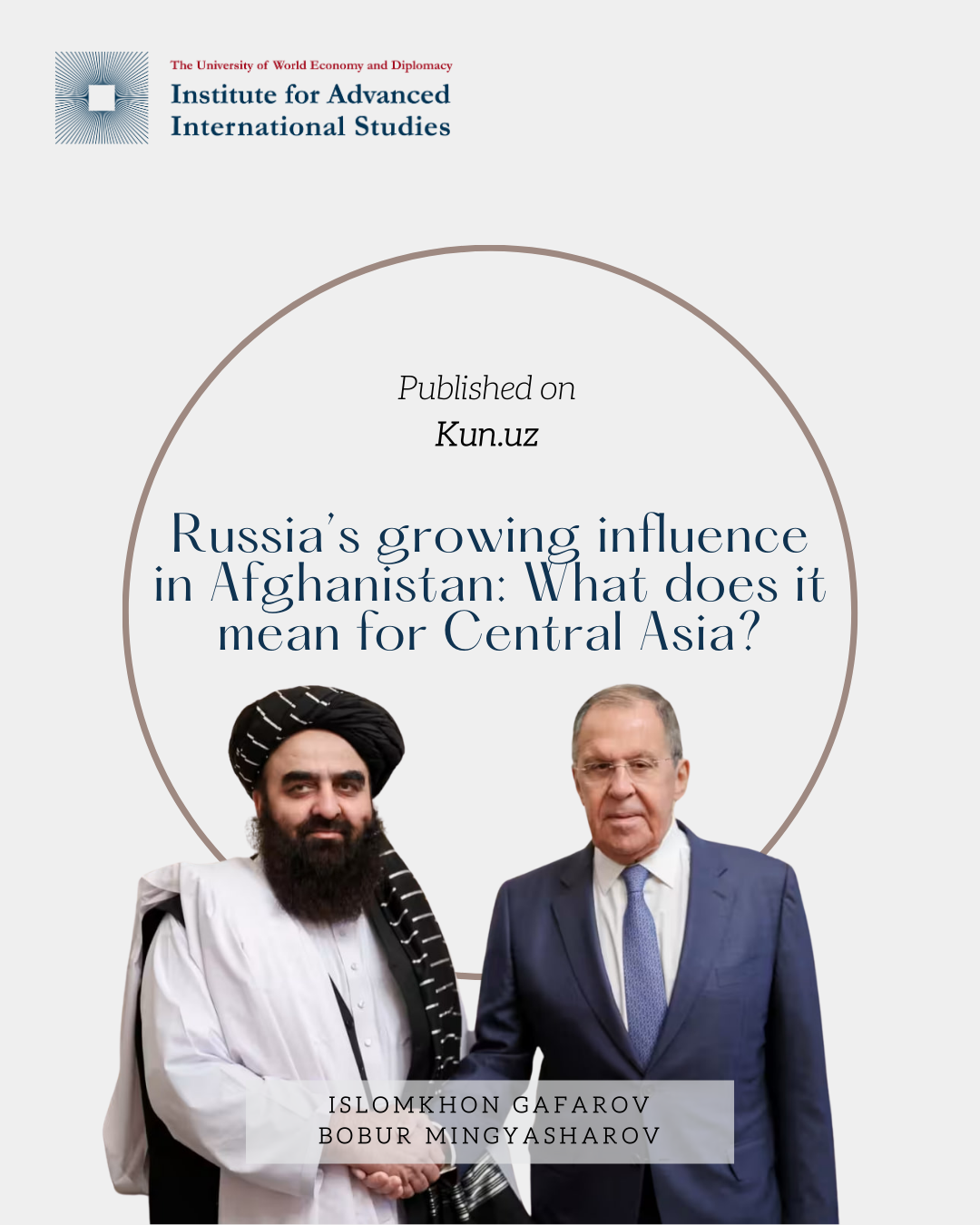

Dr. Islomkhon Gafarov, Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Afghanistan and South Asian Studies, and Junior Research Fellow Bobur Mingyasharov state that Russia’s growing influence in Afghanistan is a strategic shift shaped by both geopolitical necessity and economic interests. Following the U.S. withdrawal, Moscow has sought to expand its engagement with the Taliban government, leveraging Afghanistan’s transit potential and market of 41 million people. The authors argue that Russia’s pragmatic approach — maintaining diplomatic presence in Kabul and considering the removal of the Taliban from its terrorist list — demonstrates a long-term commitment to strengthening ties. This shift, they note, aligns with Russia’s broader strategy of consolidating influence in Eurasia amid its ongoing confrontation with the West.

The authors further state that Russia’s engagement with Afghanistan encompasses three primary areas: trade, resource extraction, and security cooperation. They highlight that trade turnover between the two countries has exceeded $1 billion, with projections to reach $10 billion by 2030. Russia’s interest in Afghanistan’s lithium and rare earth minerals, they note, positions it in direct competition with China and India for resource access. Additionally, the authors emphasize Russia’s humanitarian aid efforts as part of its “soft power” strategy to improve relations with the Afghan authorities and overcome lingering historical grievances from the Soviet-Afghan war.

They also highlight that Russia’s strategy is shaped by competition with China, particularly in the economic sphere. While Beijing has firmly established itself as a key investor in Afghanistan through the Belt and Road Initiative, Russia seeks to secure its own economic foothold, particularly by supporting large-scale infrastructure projects such as the Trans-Afghan Railway. This project, they argue, would enhance Russia’s access to Indian and Pakistani markets while reinforcing Central Asia’s role as a transit corridor. However, they caution that the evolving geopolitical landscape in Afghanistan — where Russia, China, India, and Pakistan all vie for influence — could create tensions that may spill over into Central Asia.

Furthermore, it is underlined that security concerns remain a central factor in Russia’s Afghanistan policy. They note that Moscow views the Taliban as a critical partner in countering ISIS-Khorasan, particularly following the Crocus City Hall terrorist attack in Moscow. While Russia has refrained from expanding its military presence in Central Asia, the authors argue that its diplomatic engagement with the Taliban could reshape regional security dynamics. Finally, they conclude that Russia’s growing involvement in Afghanistan presents both opportunities and challenges for Central Asia, particularly in the realms of economic cooperation, counterterrorism, and water resource management.

Read the policy brief on Kun.uz

* The Institute for Advanced International Studies (IAIS) does not take institutional positions on any issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IAIS.